I'm not quite halfway through The Best American Essays of the Century, a book that I bought at Bookman's for nine dollars in trade credit over a year ago, maybe more. I bought it because I teach people how to write essays, and I have a philosophy of learning that involves learning from examples, and examples labeled "the best" by Joyce Carol Oates and Robert Atwan are worth learning from. I gave myself permission to read an essay a day or so. I have not kept that pace, but I do find the time to read here and there, so I'm slowly making my way through.

I have made discoveries while reading this book--really, while piling the readings up in my head, one essay by one essay, each a few years down the road from the one I read before it, each a record of how ideas are moving along the century.

1. Race Relations and Civil Rights permeate much deeper into the soil of American History than I realized (or was taught, really). It seems like one of every three or four essays tackles some varied perspective on minorities and majorities in our nation. The four that stick in my head are W.E.B. Du Bois's "On the Coming of John" (education, black/white, poverty), John Jay Chapman's "Coatesville" (repentence of racial crimes whose perpetrators were acquitted), Richard Wright's "The Ethics of Living Jim Crow: An Autobiographical Sketch" (education of a different, social, everyday sort), and Langston Hughes's "Bop" (pop culture's roots in dark dark things)

2. Writing that is worth reading is the process of a careful mind exploring simple moments, questions, or ideas. The ideas themselves do not need to be complicated. Hughes lays out a conversation between two black men about bebop music. James Agee, in "Knoxville: Summer of 1915," puts the evenings in his boyhood neighborhood under the poetic miscroscope. E.B. White writes about revisiting a lake, a place that he visited with his father, as a father himself in "Once More to the Lake." These are not complicated things, but the essays are beautiful, exact, detailed, and careful.

3. Organization is any structure an author uses to prop up his ideas; there are no rules--only control. I've told students before that, while teachers may ask for certain parts of particular structures, in the real world, all that readers ask is that the author seem like he is in control, that he knows where the writing is going. However an author can do that is okay by the public. These essays are examples of that. Wright goes so far as to build his essay in sections marked by roman numerals. They are conversational in tone and include dialect in dialogue, and are of varied length, but the roman numerals shows the reader that Wright knows where he's starting and stopping. He knows the limits of each story, and he lets each one live fully within those limits.

I think these discoveries could work to benefit a class full of learning writers.

The fact that race relations is such an integral thread to American life could spur a class to write about their own experiences living in multicultural environments, about their own life-lessons about "how it is" in terms of stereotypes and racial interactions and what can be done to move "how it is" toward "how it could be."

The idea of growing an essay from a simple idea could be important to the direction given. The work a student should do is not the work of diciphering an assigment; instead, it should be the work of taking a simple question or idea (either given by a teacher or unearthed from life) and mapping it, dissecting it, exploring it, and recording what is found.

Organization and control may be the most difficult to grade, but may also be fun to teach. It would allow a conversation between teacher and student in which the student is the owner of the idea--and of the presentation of the idea--and the teacher is the mentor+audience. In this mode, the student can discover and attempt to record, and the teacher can react, ask questions, and give gentle suggestions to mold people who can control the wild ideas in their heads that sneak around like mice or flail like loosed fire hoses. The only rule is: learn to control the idea, to package it so it can be unpacked and understood.

Monday, December 22, 2008

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

And They See That It Is Good, So They Try To Cram It All Into Their Allotted Two-to-Three Pages

Focus is one of the most addressed issues in the DV Writing Lab. Often, student writers come in with a draft that they cranked out at home and ask us to "check it." What they mean is: Find my mistakes, oh writing nerd (basically, if not in those exact words). What they need more times than not, however is: focus.

I usually make people talk through their papers before we read them to see how much control they have of their ideas apart from the pages on which they flung their words in a coffee-infused, television-distracted, text-message-interrupted whirl of keystrokes. I ask them, "What is your paper about?" It's a simple question based on the precision of the second-person pronoun that ninety-nine percent of the time results in a student regurgitating the question or prompt given them by their instructor, or spitting out a one-to-three word phrase such as "construction" or "global warming" or "legalization of pot."

The former could go anywhere, really, but the latter, after combining their answers to my questions with a quick review of their essay, leads to a discussion of the idea of focus, a slippery rascal that is deceptively simple ("focus" is not some esoteric literary term) to the point that it could be slipped into a lesson on writing by a teacher and assumed to be understood without a hitch.

Even the student could assume they get it. They fill a few pages with their thoughts on construction work. They tell some stories, build their credibility with experiences working alongside construction-working fathers and injuries earned with the mis-hit of a hammer (or even worse, injuries observed in coworkers involving nail guns or falling _____ stories). They slip in a sentence here and there about how the foreman's job is to keep people safe and make sure the job gets done, and they have an essay on Why They Want To Be A Foreman. Done done and done.

Here is where one of the more important discoveries about writing I've made while tutoring full-time comes in. They assume that, because they did not talk about anything but construction, they have achieved focus. The problem is that the essay is not supposed to be a collection everything they know about construction (or global warming or pot or anything else). It's supposed to explain why this certain author wants to be a foreman on a construction crew--not a worker and not the project manager, but the foreman, who has specific responsibilities and duties.

The stories about smashing thumbs and nearly missing getting impaled with nails were interesting and detailed and appeared to be on topic, and they could be, if the student sees how to focus. Everything goes back to the central idea. Everything. If it's in the neighborhood, that's not focus. That's blurred edges.

This happens with essays about mothers and fiances, jobs and family vacations, hopes for future jobs, favotire holidays, scars, characters in books, and everything else that students are asked to write about. They see stories they want to tell or facts that they think would be interesting or information that they assume is indispensable and try to get it all down on the pages, all of it all of it all of it, and it's too much because they thought about the general topic, but not about what they are specifically saying about that person or thing or idea.

I usually make people talk through their papers before we read them to see how much control they have of their ideas apart from the pages on which they flung their words in a coffee-infused, television-distracted, text-message-interrupted whirl of keystrokes. I ask them, "What is your paper about?" It's a simple question based on the precision of the second-person pronoun that ninety-nine percent of the time results in a student regurgitating the question or prompt given them by their instructor, or spitting out a one-to-three word phrase such as "construction" or "global warming" or "legalization of pot."

The former could go anywhere, really, but the latter, after combining their answers to my questions with a quick review of their essay, leads to a discussion of the idea of focus, a slippery rascal that is deceptively simple ("focus" is not some esoteric literary term) to the point that it could be slipped into a lesson on writing by a teacher and assumed to be understood without a hitch.

Even the student could assume they get it. They fill a few pages with their thoughts on construction work. They tell some stories, build their credibility with experiences working alongside construction-working fathers and injuries earned with the mis-hit of a hammer (or even worse, injuries observed in coworkers involving nail guns or falling _____ stories). They slip in a sentence here and there about how the foreman's job is to keep people safe and make sure the job gets done, and they have an essay on Why They Want To Be A Foreman. Done done and done.

Here is where one of the more important discoveries about writing I've made while tutoring full-time comes in. They assume that, because they did not talk about anything but construction, they have achieved focus. The problem is that the essay is not supposed to be a collection everything they know about construction (or global warming or pot or anything else). It's supposed to explain why this certain author wants to be a foreman on a construction crew--not a worker and not the project manager, but the foreman, who has specific responsibilities and duties.

The stories about smashing thumbs and nearly missing getting impaled with nails were interesting and detailed and appeared to be on topic, and they could be, if the student sees how to focus. Everything goes back to the central idea. Everything. If it's in the neighborhood, that's not focus. That's blurred edges.

This happens with essays about mothers and fiances, jobs and family vacations, hopes for future jobs, favotire holidays, scars, characters in books, and everything else that students are asked to write about. They see stories they want to tell or facts that they think would be interesting or information that they assume is indispensable and try to get it all down on the pages, all of it all of it all of it, and it's too much because they thought about the general topic, but not about what they are specifically saying about that person or thing or idea.

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

Mustachioed!

This guy came in today in all black, including his backpack, his long hair, and his mustache. It got me wondering (as things often do) about mustaches. This guy is one of many guys, my father included, who sports a mustache, but it is not exclusive to a particular style (I have never once seen my father in all black, and his hair is not long like a Seattle grunge rocker but trimmed short and neat).

Here is where this is going: Why the mustache?

I would love to give that option to students to investigate. What is the history of the male decision to grow the hair above the lip, yet shave the hair below and around? When? Why? What does it mean? How has that meaning changed? Where did the word "mustache" come from?

Does it sound goofy? Yes. Would it lead them to all kinds of places? Yes: history, culture, social behavior, fashion, trends, etc. It would also be more fun to read than yet another paper about abortion/global warming/lowering the drinking age/legalizing pot.

Here is where this is going: Why the mustache?

I would love to give that option to students to investigate. What is the history of the male decision to grow the hair above the lip, yet shave the hair below and around? When? Why? What does it mean? How has that meaning changed? Where did the word "mustache" come from?

Does it sound goofy? Yes. Would it lead them to all kinds of places? Yes: history, culture, social behavior, fashion, trends, etc. It would also be more fun to read than yet another paper about abortion/global warming/lowering the drinking age/legalizing pot.

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

Now You See, Me Now You Don't v. Up, Up, and Away

If I were in a classroom environment where I was charged with teaching people how to argue, I would start here, I think.

Invisibility v. Flight

You get one of these superpowers. Pick one. Quick, pick one, no thinking. Now, write down the reasons you picked this one.

This is the gut reaction part. We would use this part to talk about how people often have opinions before they think through their reasons, but there are reasons buried in the heads of those people. This is the part where I get the students to realize that opinions and even guesses don't come out of nowhere, and that they can be unearthed with a little work. (Then we do a little work to unearth our reasons for our gut decisions, our choice of invisibility v. flight.)

Let's listen to some other people make this decision: This American Life's "Superpowers" Episode.

Act One of this epidsode is thirteen minutes of people choosing invisibility or flight. This is the part where we listen to how other people think through choices. Students would write down all the reasons they hear and make note of reasons they did not think of and any reasons they would choose for themselves after hearing them on the show.

Now, think of reasons why someone would pick the other superpower. Not the one you picked. The other one.

This is the part where we think of The Other Side, where we learn to think through the opinions of others, even if we don't agree with them. Students have to come up with reasons for the other power (at this point, some could be waffling on their original choice, but I would simply have them examine the one they didn't go to on their gut instincts).

Taking all of this into account, now you get to make a new choice. Invisibility or flight? You also get to come up with intelligent reasons for your choice. That will turn into a fun-yet-intelligent essay.

This is the part where they work on producing a piece of writing based on all this thinking. We'd probably work on outlining and revising and proofreading, but the basic idea of all this is that Invisibility v. Flight is not a supercomplex issue for them to deal with, but a simple choice that turns into a more complex and mature thought process.

We could also:

-have a class debate

-look at the benefits of both superpowers in actual comic books (in the lives of "real" superheros) -imagine the drawbacks of each power in everyday life (outside the lives of superheros)

-imagine the benefits of each power to a regular, non-hero-type person

-establish rules for each power (what would and would not turn invisible with you, how fast and high you could fly, etc.)

-move on to discussing something a little weightier like the agreeing or disagreeing with the claim that begins F. Scott Fitzgerald's essay "The Crack-Up": "Of course all life is a process of breaking down..."

Invisibility v. Flight

You get one of these superpowers. Pick one. Quick, pick one, no thinking. Now, write down the reasons you picked this one.

This is the gut reaction part. We would use this part to talk about how people often have opinions before they think through their reasons, but there are reasons buried in the heads of those people. This is the part where I get the students to realize that opinions and even guesses don't come out of nowhere, and that they can be unearthed with a little work. (Then we do a little work to unearth our reasons for our gut decisions, our choice of invisibility v. flight.)

Let's listen to some other people make this decision: This American Life's "Superpowers" Episode.

Act One of this epidsode is thirteen minutes of people choosing invisibility or flight. This is the part where we listen to how other people think through choices. Students would write down all the reasons they hear and make note of reasons they did not think of and any reasons they would choose for themselves after hearing them on the show.

Now, think of reasons why someone would pick the other superpower. Not the one you picked. The other one.

This is the part where we think of The Other Side, where we learn to think through the opinions of others, even if we don't agree with them. Students have to come up with reasons for the other power (at this point, some could be waffling on their original choice, but I would simply have them examine the one they didn't go to on their gut instincts).

Taking all of this into account, now you get to make a new choice. Invisibility or flight? You also get to come up with intelligent reasons for your choice. That will turn into a fun-yet-intelligent essay.

This is the part where they work on producing a piece of writing based on all this thinking. We'd probably work on outlining and revising and proofreading, but the basic idea of all this is that Invisibility v. Flight is not a supercomplex issue for them to deal with, but a simple choice that turns into a more complex and mature thought process.

We could also:

-have a class debate

-look at the benefits of both superpowers in actual comic books (in the lives of "real" superheros) -imagine the drawbacks of each power in everyday life (outside the lives of superheros)

-imagine the benefits of each power to a regular, non-hero-type person

-establish rules for each power (what would and would not turn invisible with you, how fast and high you could fly, etc.)

-move on to discussing something a little weightier like the agreeing or disagreeing with the claim that begins F. Scott Fitzgerald's essay "The Crack-Up": "Of course all life is a process of breaking down..."

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

Meaning is Everywhere, Even in Honey Jars or Cartoon Savannas

Here are two thesis ideas for essays I overheard in the Writing Lab today:

1. All the major characters from Winnie the Pooh are different aspects of Christopher Robin's personality. The person who said this went through an exhaustive list of each character and which part of Christopher Robin's personality they correspond to. It was really quite impressive.

2. The Lion King is Shakespeare's Hamlet in Africa. And Disney-fied. No, Simba doesn't feign insanity, or put on a play-within-a-play/movie, and he doesn't die in the end, and Scar doesn't marry Simba's mother, but there are enough similarities between the two stories there for that argument to stand (there is a father's ghost in each, which is important for any comparison including Hamlet).

1. All the major characters from Winnie the Pooh are different aspects of Christopher Robin's personality. The person who said this went through an exhaustive list of each character and which part of Christopher Robin's personality they correspond to. It was really quite impressive.

2. The Lion King is Shakespeare's Hamlet in Africa. And Disney-fied. No, Simba doesn't feign insanity, or put on a play-within-a-play/movie, and he doesn't die in the end, and Scar doesn't marry Simba's mother, but there are enough similarities between the two stories there for that argument to stand (there is a father's ghost in each, which is important for any comparison including Hamlet).

Friday, November 14, 2008

Collaborate + Imitate: Two Ideas for Possibilities in Teaching Writing

{Collaborate}

Two Writing 100 classes each write their first paragraphs, say, on how they got an important/prominent/significant scar (an actual assignment in Andrea Graham's classes). They discuss the assignment, generate some ideas (the one on my leg from the bike wreck, or the one over my left eye from saving that stray dog in the alley?), and bang out a draft.

Then, they trade. Class A gets Class B's paragraphs, while Class B sends their paragraphs to Class A. Both classes dissect from first sentence to last. Both groups ask what is there and what is not there, what is done well and what questions still hang in the blank white space between the black ink marks. Class A's writers get to mentally pick apart, to explore, to venture questions, without the worry of knowing their paragraph is somewhere in the room, lurking incomplete and imperfect. Class B's writers learn how to dissect--really, is there a more perfect verb for this action?--what others have put on a page but are not present to elaborate on or defend: what is on the page is all they have as readers, and thus they (hopefully) see that is all they give as writers, so they should take care to put on the page what they want others to pick off the page. Both classes learn to ask specific questions, to look for the pieces that should be there, to encourage and applaud what is truly good with better phrases than "That's good!"

The student-dissectors return the paragraphs and then revise. So much of writing is learned in revision. Most, I would venture. Everything before is just experiment and hope.

In doing this write-and-switch between classes, the process of looking closely at incomplete and imperfect work is taught, is focused on and addressed thoroughly. Student writers need that from their experienced mentor-writers and -scholars.

{Imitate}

People learn by observing and repeating. Only the truly brave or brash or innovative enjoy striking out on their own. Most of us are intimidated or simply expect the coming failure.

So: Controlled Imitation. I often wonder about the use of non-textbook texts in Writing classes (because those books and magazines and Internet columns are written by people who want to write for some specific purpose), and that wondering has honed in on the idea of letting a class loose with a teacher-chosen set of magazines, books, and even Internet columns, asking them to read and make note of articles that catch their attention (and their attention is caught), and then asking them to choose one to imitate.

They can observe and learn from a specific text. They can get inside it, figure out why it works, and then try to build the same type of rhetorical machine. I think I would start by having them type parts of, or maybe even the entire text*. That way, they could feel what writing these kind of polished sentences and specific details is like. Then, we could look at the ideas contained in that piece and the students could learn to think along the lines that writers who want to write (and get paid to write) use to sniff out stories, construct arguments, and string readers along through their entire piece. In addition to ideas (but after after after), we could get to technical stuff: organization, paragraph development, sentences, intro+conclusion. Then, they would be off to write a similar piece from their own slant or about their own subject.

It's a launching pad, really. Also an apprenticeship in a way.

I think there is space for this in the learning process.

*Watch Finding Forrester.

Two Writing 100 classes each write their first paragraphs, say, on how they got an important/prominent/significant scar (an actual assignment in Andrea Graham's classes). They discuss the assignment, generate some ideas (the one on my leg from the bike wreck, or the one over my left eye from saving that stray dog in the alley?), and bang out a draft.

Then, they trade. Class A gets Class B's paragraphs, while Class B sends their paragraphs to Class A. Both classes dissect from first sentence to last. Both groups ask what is there and what is not there, what is done well and what questions still hang in the blank white space between the black ink marks. Class A's writers get to mentally pick apart, to explore, to venture questions, without the worry of knowing their paragraph is somewhere in the room, lurking incomplete and imperfect. Class B's writers learn how to dissect--really, is there a more perfect verb for this action?--what others have put on a page but are not present to elaborate on or defend: what is on the page is all they have as readers, and thus they (hopefully) see that is all they give as writers, so they should take care to put on the page what they want others to pick off the page. Both classes learn to ask specific questions, to look for the pieces that should be there, to encourage and applaud what is truly good with better phrases than "That's good!"

The student-dissectors return the paragraphs and then revise. So much of writing is learned in revision. Most, I would venture. Everything before is just experiment and hope.

In doing this write-and-switch between classes, the process of looking closely at incomplete and imperfect work is taught, is focused on and addressed thoroughly. Student writers need that from their experienced mentor-writers and -scholars.

{Imitate}

People learn by observing and repeating. Only the truly brave or brash or innovative enjoy striking out on their own. Most of us are intimidated or simply expect the coming failure.

So: Controlled Imitation. I often wonder about the use of non-textbook texts in Writing classes (because those books and magazines and Internet columns are written by people who want to write for some specific purpose), and that wondering has honed in on the idea of letting a class loose with a teacher-chosen set of magazines, books, and even Internet columns, asking them to read and make note of articles that catch their attention (and their attention is caught), and then asking them to choose one to imitate.

They can observe and learn from a specific text. They can get inside it, figure out why it works, and then try to build the same type of rhetorical machine. I think I would start by having them type parts of, or maybe even the entire text*. That way, they could feel what writing these kind of polished sentences and specific details is like. Then, we could look at the ideas contained in that piece and the students could learn to think along the lines that writers who want to write (and get paid to write) use to sniff out stories, construct arguments, and string readers along through their entire piece. In addition to ideas (but after after after), we could get to technical stuff: organization, paragraph development, sentences, intro+conclusion. Then, they would be off to write a similar piece from their own slant or about their own subject.

It's a launching pad, really. Also an apprenticeship in a way.

I think there is space for this in the learning process.

*Watch Finding Forrester.

Logo!

My friend Andrew is a graphic designer. A few months ago, I asked him if he would design a seal-like logo for the Writing Center. Here is result of our discussion.

Some thoughts on our logo:

1. The griffin was Andrew's doing, but I'm all in favor of griffins. They are my favorite mythological creature (I'm not making that up), and what could be better than a griffin holding a pencil. Write, griffin, write!

2. I wanted to make sure the year of establishment was on there because a) it's kind of what you do on a seal, and b) I am grateful to the people who came before me and decided that a Writing Center with a Writing Lab Specialist would be a good idea.3. Tucson is on there not only because we do what we do in the Old Pueblo, but because we want people to be proud of doing what they do in the Old Pueblo.

4. "Escribimos Amigos" isn't any kind of official motto, but it is fun to say. Say it. Go ahead. Say it under your breath if you have to (maybe you are at work and or in the library and you want to remain quiet out of respect for others). It means, "We write, friends" in Español. Also: it rhymes (sort of, depending on how loose you are with your definition of rhyming--I have a friend who adamantly denies the rhyming nature of "alligator" and "calculator").

5. We hope to eventually put this on shirts. A former student of mine has a screen-printing business, so it may pop up soon on someone's clothes.

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Ask the Photographer

A student came in yesterday with the assignment to come up with a list of questions for the person who took a photograph (she didn't have the picture, but said it was of galaxies).

I see many, many people who say, "I don't know" and see it as a stopping point. They give up instead of inquire further. I like this assignment because it was a low-pressure chance to practice being curious. Students need to be inquisitive explorers to be successful, and this was a dry-run at questioning, a way to stretch the students' brains powers of exploration. This is an especially important skill for students who write research papers, have to choose their own topics, or write about issues they don't know about (which is kind of, pretty much, all students).

I also like this because it is repeatable to the nth degree (with n equalling the number of photographs available to the instructor).

I see many, many people who say, "I don't know" and see it as a stopping point. They give up instead of inquire further. I like this assignment because it was a low-pressure chance to practice being curious. Students need to be inquisitive explorers to be successful, and this was a dry-run at questioning, a way to stretch the students' brains powers of exploration. This is an especially important skill for students who write research papers, have to choose their own topics, or write about issues they don't know about (which is kind of, pretty much, all students).

I also like this because it is repeatable to the nth degree (with n equalling the number of photographs available to the instructor).

Thursday, November 6, 2008

On the Kind of Attention That Needs to Be Paid

Here is what I tell students who are somewhere in the area of proofreading their work (which they sometimes want us to help with, but more often assume we just do for them):

1. Read Out Loud

It makes your brain process the words again. You need to make your brain do that because your brain is smart and it knows what you want to say. Now, though, you are interested in what you actually did say, not what you wanted to say. When you read out loud, your brain sends the words to your mouth instead of keeping them up in your head.

A high percentage of students tell me that they don't like to read out loud. I tell them that it doesn't really matter if they like it. It's an important step to take to owning the little black marks you printed on a page. Oh, and after I make them start reading, when they see the first few mistakes, they forget about liking or not liking and simply read.

2. Read Slowly

The goal is not to read through your paper so you can say you read through your paper. The goal is to catch little mistakes, and to do that, you need to set your brain to a different mode of reading than when you cruise through a magazine article, brush over an email, or scan an assigned chapter about mitosis for Biology class. To do that, you need to read slowly. You need to make yourself read slowly. At some point, you will speed up. I guarantee it. A paragraph or two into your paper, you'll gain speed like a cyclist riding down a mountain. Hit the brakes. Slow down. If you don't, you'll miss things you are perfectly capable of fixing.

3. Expect Little Mistakes

Finding a mistake is not finding a failure. Finding a mistake is simply finding a spot where you hit the wrong key or forgot a word, or forgot to delete a word, or make a word plural, or etc., etc. When you proofread, you are looking for the missing "s" at the end of a word or the accidental "-ed" that makes the right verb into the wrong tense. You're trying to make sure you put periods where periods should go, that commas are in the right places, and the words that need to be capitalized are capitalized (and the ones that don't need it are not).

These are small, small things. Look closely. Look very closely. They are there. You can find them and fix them.

1. Read Out Loud

It makes your brain process the words again. You need to make your brain do that because your brain is smart and it knows what you want to say. Now, though, you are interested in what you actually did say, not what you wanted to say. When you read out loud, your brain sends the words to your mouth instead of keeping them up in your head.

A high percentage of students tell me that they don't like to read out loud. I tell them that it doesn't really matter if they like it. It's an important step to take to owning the little black marks you printed on a page. Oh, and after I make them start reading, when they see the first few mistakes, they forget about liking or not liking and simply read.

2. Read Slowly

The goal is not to read through your paper so you can say you read through your paper. The goal is to catch little mistakes, and to do that, you need to set your brain to a different mode of reading than when you cruise through a magazine article, brush over an email, or scan an assigned chapter about mitosis for Biology class. To do that, you need to read slowly. You need to make yourself read slowly. At some point, you will speed up. I guarantee it. A paragraph or two into your paper, you'll gain speed like a cyclist riding down a mountain. Hit the brakes. Slow down. If you don't, you'll miss things you are perfectly capable of fixing.

3. Expect Little Mistakes

Finding a mistake is not finding a failure. Finding a mistake is simply finding a spot where you hit the wrong key or forgot a word, or forgot to delete a word, or make a word plural, or etc., etc. When you proofread, you are looking for the missing "s" at the end of a word or the accidental "-ed" that makes the right verb into the wrong tense. You're trying to make sure you put periods where periods should go, that commas are in the right places, and the words that need to be capitalized are capitalized (and the ones that don't need it are not).

These are small, small things. Look closely. Look very closely. They are there. You can find them and fix them.

Friday, October 31, 2008

On the Use of Two-Word Sentences

While I was teaching Writing Fundamentals in the spring, I ran across an article on Esquire.com entitled, "On Saying No," which explores what happens when one stops explaining and simply says "No," and begins like this:

"I had a high school English teacher named Mr. Turk, who insisted that the best sentences in the world were just two words. Subject and verb. He said our class had proven too dense to understand prepositions. 'We define the limitations of experience with action,' he said. So he had us practice one afternoon, on a single piece of paper, writing these two-word sentences, which he considered elemental. Irreplaceable, even. "Two words," he said. I worked.

"I do. I insist. You will. She flew."

I was intrigued at the time because, as a part of learning as a tutor, I had set up a meeting with an ESL instructor here at Desert Vista to talk with the Writing tutors about how she works with ESL students in her classes. She showed us how, to begin, she took them to the core of writing: two words, subject + verb. Everything they did after was adding more information onto the subject + verb combination. The Esquire article and the peek inside the ESL teacher's head inspired me to ask my Writing 100 students to build two-word sentences as a simple start-of-class journal assignment (I just wanted to see where it would go; I live much of my life as a writer working on a draft: see something interesting, try it out, see where it goes, learn, revise, revise, revise).

It went. I explained the assignment to my students. Ten two-word sentences, subject and verb, no repeated words. Some understood, and some looked at me like I was crazy. Two words? That's it? I told them to try it. They tried. Some wrote a mixture of subject+verb, adjective+noun or adverb+verb. Some coasted through, crafting simple sentences without investing much in the choice of subject or verb, or diving too far in to the relationship of the subject to the verb, much like the sample sentences from "On Saying No," pronouns or names attached to general verbs that apply to most people or things, verbs without much substance or verve.

Some, however, did as much as possible with their allotted word count. They wrote "Architects designed" or "Astronauts launched." They connected specific subjects to actions that those subjects were more likely to do than your average person on the street. They explored. They worked. They wrote.

I am thinking of these two-word sentences now for several reasons:

1. I often work with people who do not fully understand subjects and verbs.

2. I see people who put words down on paper, yet do not fully understand the meaning of what they are putting down on paper.

3. I help people learn to see how sentences can string together to form a thread of thought.

4. I think writing two-word sentences could be a useful strategy in a developmental Writing classroom becauses it asks for focus yet provides efficiency--there are no extra words getting in the way.

5. Building two-word sentences, and I mean the good ones, the specific ones that maximize their size, helps people understand one of the key principles of editing: use only meaningful words that you need. No fluff. I like to think of writers editing their papers like runners think of their training their bodies: lean, fast, no extra muscle-for-the-sake-of-muslce, only what is necessary for the purpose of running fastfastfast or farfarfar.

The idea of the two-word sentence has been swimming around in my brain for awhile, and, for a combination of those reasons, has now bobbed to the surface.

They could be used to help people see the different stages in a process (a part of learning to write is learning to think, which involves differentiating between Step No.1, Step No.2, Step No.3, etc.; people must see these before they can organize a paper around them). This could be done by supplying the subjects (say, the people involved in building something or the ingredients in meal--who knows what else) and asking for the verbs that mark the stages of the process. This morning I thought of showing scenes from films, choosing 2- or 5- or even 10-minute chunks of all kinds of movies, and asking for a summary built of only two-word sentences.

They could be used to discuss the possible strength of verbs (thank you Pat C. Fellers for teaching me not to settle for am, are, is, was, were, have, has, had, be, being, been and instead digging and rearranging to fit a strong, specific verb in my sentences). Verbs are the strongest words (again, according to Mr. Turk, "We define the limitations of experience with action.") we can write, and stronger writers are made by asking student writers to find stronger words, more efficient words, words that can carry more weight for longer distances. This could be done by supplying specific subjects--from architects and astronauts to zoologists and zephyrs--and, again, simply asking for correlating verbs (or supplying verbs--from analyze and ascend to zigzag and zap--and asking for appropriate subjects).

They could also be used to ask budding writers to observe their world by sending them out into the field--campus, mall, baseball game, the bus ride across town--to identify specific nouns and their specific actions, and return with a notepad full of two-word sentences in which can be glimpsed the life, population, action, and general feel of the area they just spent their time in.

I'm a believer in using simple processes (simple machines! walking! dragging a pen across paper!) to accomplish larger and more complicated things. The two-word sentence could be one of the simple machines of writing, highly-efficient and easily adaptable and thus able to work well to serve an unknowable number of purposes.

"I had a high school English teacher named Mr. Turk, who insisted that the best sentences in the world were just two words. Subject and verb. He said our class had proven too dense to understand prepositions. 'We define the limitations of experience with action,' he said. So he had us practice one afternoon, on a single piece of paper, writing these two-word sentences, which he considered elemental. Irreplaceable, even. "Two words," he said. I worked.

"I do. I insist. You will. She flew."

I was intrigued at the time because, as a part of learning as a tutor, I had set up a meeting with an ESL instructor here at Desert Vista to talk with the Writing tutors about how she works with ESL students in her classes. She showed us how, to begin, she took them to the core of writing: two words, subject + verb. Everything they did after was adding more information onto the subject + verb combination. The Esquire article and the peek inside the ESL teacher's head inspired me to ask my Writing 100 students to build two-word sentences as a simple start-of-class journal assignment (I just wanted to see where it would go; I live much of my life as a writer working on a draft: see something interesting, try it out, see where it goes, learn, revise, revise, revise).

It went. I explained the assignment to my students. Ten two-word sentences, subject and verb, no repeated words. Some understood, and some looked at me like I was crazy. Two words? That's it? I told them to try it. They tried. Some wrote a mixture of subject+verb, adjective+noun or adverb+verb. Some coasted through, crafting simple sentences without investing much in the choice of subject or verb, or diving too far in to the relationship of the subject to the verb, much like the sample sentences from "On Saying No," pronouns or names attached to general verbs that apply to most people or things, verbs without much substance or verve.

Some, however, did as much as possible with their allotted word count. They wrote "Architects designed" or "Astronauts launched." They connected specific subjects to actions that those subjects were more likely to do than your average person on the street. They explored. They worked. They wrote.

I am thinking of these two-word sentences now for several reasons:

1. I often work with people who do not fully understand subjects and verbs.

2. I see people who put words down on paper, yet do not fully understand the meaning of what they are putting down on paper.

3. I help people learn to see how sentences can string together to form a thread of thought.

4. I think writing two-word sentences could be a useful strategy in a developmental Writing classroom becauses it asks for focus yet provides efficiency--there are no extra words getting in the way.

5. Building two-word sentences, and I mean the good ones, the specific ones that maximize their size, helps people understand one of the key principles of editing: use only meaningful words that you need. No fluff. I like to think of writers editing their papers like runners think of their training their bodies: lean, fast, no extra muscle-for-the-sake-of-muslce, only what is necessary for the purpose of running fastfastfast or farfarfar.

The idea of the two-word sentence has been swimming around in my brain for awhile, and, for a combination of those reasons, has now bobbed to the surface.

They could be used to help people see the different stages in a process (a part of learning to write is learning to think, which involves differentiating between Step No.1, Step No.2, Step No.3, etc.; people must see these before they can organize a paper around them). This could be done by supplying the subjects (say, the people involved in building something or the ingredients in meal--who knows what else) and asking for the verbs that mark the stages of the process. This morning I thought of showing scenes from films, choosing 2- or 5- or even 10-minute chunks of all kinds of movies, and asking for a summary built of only two-word sentences.

They could be used to discuss the possible strength of verbs (thank you Pat C. Fellers for teaching me not to settle for am, are, is, was, were, have, has, had, be, being, been and instead digging and rearranging to fit a strong, specific verb in my sentences). Verbs are the strongest words (again, according to Mr. Turk, "We define the limitations of experience with action.") we can write, and stronger writers are made by asking student writers to find stronger words, more efficient words, words that can carry more weight for longer distances. This could be done by supplying specific subjects--from architects and astronauts to zoologists and zephyrs--and, again, simply asking for correlating verbs (or supplying verbs--from analyze and ascend to zigzag and zap--and asking for appropriate subjects).

They could also be used to ask budding writers to observe their world by sending them out into the field--campus, mall, baseball game, the bus ride across town--to identify specific nouns and their specific actions, and return with a notepad full of two-word sentences in which can be glimpsed the life, population, action, and general feel of the area they just spent their time in.

I'm a believer in using simple processes (simple machines! walking! dragging a pen across paper!) to accomplish larger and more complicated things. The two-word sentence could be one of the simple machines of writing, highly-efficient and easily adaptable and thus able to work well to serve an unknowable number of purposes.

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

On Beer and Research

Another set of valid research questions that are based in reality came from a student working a paper persuading her friends not to do drugs. The questions are tangents, but they are worth mentioning because they a) are genuine, and b) seem like they might have simple answers, but really don't, so they require some research.

Her questions:

1. Why did people make beer?

2. Why do people drink beer?

On No.1: She thought this would be a simple answer to find on the Internet, so she went sleuthing, only to find differentiations between ales and lagers and pilsners (oh my!). The history she found was brief (as in, Ancient Egyptians had beer! Look how old beer is!). She found out that her question was more complex than she originally assumed: instead of When's and Where's, she wanted the Why, which is a great thing to look for. It takes finding When's and Where's along with Reasons and Purposes. Since this wasn't her main project, she cut off her search at this point, but not before I told her about how people write books based on simple research questions like this*.

On No.2: Here, she opened the door to sociology. In her limited experience, the answer to that questions was To Get Drunk, but she sensed there was some bigger reason behind that. We talked about how there are many reasons why people drink beer, and that she could write a whole paper based on different reasons why different people drink different beers.

On Why This Paper Would Be an Interesting Paper to Read:

First, it came from a simple and genuine question. She really wanted to know this--it wasn't thrust upon her by an authority figure wielding a syllabus and white board marker--so the results of her paper would most likely have some life to it (especially if her work was mentored by someone who wanted to help her come alive as a writer and explorer).

Second, the question is not some obscure idea at the periphery of human consciousness or some difficult/too large/too complex idea that she knows nothing about. She knows about beer. She's seen people drink beer. She doesn't have to cross the gap of content knowledge to write about this subject. She's expanding her knowledge on a subject she is already familiar with, so the paper would show the tone of that expansion, not of a deer-in-headlights student bewildered by a topic they do not find intriguing or accessible.

Third, it's relevant to her demographic and her life. Imagine: classes where people pursue projects involving the deepening of their knowledge of the things of their own lives. Imagine: a young person taking the initiative to study the why's and wherefore's of the consumption of alcohol. Imagine: that young person waking up to the possibility of understanding why's and wherefore's, period, of opening up the thought processes of those around, of seeing that what we do and say is not Dumb Luck or What We Are Supposed To Do And Say, but that it has reason--conscious or unconscious--that it has cause, and that that cause can be put under a microscope to see its cell walls and its nucleus.

Fourth, she'll probably remember this paper pretty well. She might even win a few bets, or astound a few friends, or become a beer connoisseur. It's not like beer advertisements are going to go away, so every time she sees someone selling Budweiser or Heineken or Guiness on television, she'll be reminded that she knows a little something about where all that came from.

*Among those that come to mind: Salt, Cod, A History of the World in 6 Glasses.

Her questions:

1. Why did people make beer?

2. Why do people drink beer?

On No.1: She thought this would be a simple answer to find on the Internet, so she went sleuthing, only to find differentiations between ales and lagers and pilsners (oh my!). The history she found was brief (as in, Ancient Egyptians had beer! Look how old beer is!). She found out that her question was more complex than she originally assumed: instead of When's and Where's, she wanted the Why, which is a great thing to look for. It takes finding When's and Where's along with Reasons and Purposes. Since this wasn't her main project, she cut off her search at this point, but not before I told her about how people write books based on simple research questions like this*.

On No.2: Here, she opened the door to sociology. In her limited experience, the answer to that questions was To Get Drunk, but she sensed there was some bigger reason behind that. We talked about how there are many reasons why people drink beer, and that she could write a whole paper based on different reasons why different people drink different beers.

On Why This Paper Would Be an Interesting Paper to Read:

First, it came from a simple and genuine question. She really wanted to know this--it wasn't thrust upon her by an authority figure wielding a syllabus and white board marker--so the results of her paper would most likely have some life to it (especially if her work was mentored by someone who wanted to help her come alive as a writer and explorer).

Second, the question is not some obscure idea at the periphery of human consciousness or some difficult/too large/too complex idea that she knows nothing about. She knows about beer. She's seen people drink beer. She doesn't have to cross the gap of content knowledge to write about this subject. She's expanding her knowledge on a subject she is already familiar with, so the paper would show the tone of that expansion, not of a deer-in-headlights student bewildered by a topic they do not find intriguing or accessible.

Third, it's relevant to her demographic and her life. Imagine: classes where people pursue projects involving the deepening of their knowledge of the things of their own lives. Imagine: a young person taking the initiative to study the why's and wherefore's of the consumption of alcohol. Imagine: that young person waking up to the possibility of understanding why's and wherefore's, period, of opening up the thought processes of those around, of seeing that what we do and say is not Dumb Luck or What We Are Supposed To Do And Say, but that it has reason--conscious or unconscious--that it has cause, and that that cause can be put under a microscope to see its cell walls and its nucleus.

Fourth, she'll probably remember this paper pretty well. She might even win a few bets, or astound a few friends, or become a beer connoisseur. It's not like beer advertisements are going to go away, so every time she sees someone selling Budweiser or Heineken or Guiness on television, she'll be reminded that she knows a little something about where all that came from.

*Among those that come to mind: Salt, Cod, A History of the World in 6 Glasses.

Wednesday, October 8, 2008

First of All,

Yesterday, a student who had no idea what she was going to write about was worried about her introduction. Today, I asked a student who needs to revise a paper what she plans to do; she said, "First of all, I need to make it longer."

No. First of all, both of them need to figure out what they are saying. It's like they are planning trips without deciding where they are going. Actually, in the second student's case, she took the trip with only a vague idea of where she was going, didn't really map out her route, and didn't remember her trip well enough to make it worth her while.

For the first student, the one who worried about her introduction: Her teacher was standing with us. I asked the student which one, her teacher or me, she could introduce better. She said her teacher. All she could do for me, since she just met me, was remember my name and my job. Not an absolute failure of an intro, but not a thorough one, either. I told her she shouldn't worry about introducing something she doesn't know well. She should figure out what she has to say (she was leaning toward arguing something about coaching methods for children, about keeping it about teamwork and the like instead of becoming a raging lunatic who only cares about winning and forgets that the kids are more interesting in the orange slices after the game) before she tries to write her intro. I told her to write her introduction last if she wanted. She seemed calmer and more willing to explore an idea instead of stressed about completing a paper.

For the second student, the one who wanted to first of all make it longer: longer about nothing is worth nothing, so first of all, we talked about her core idea. Second of all, we broke down what she meant and where she could take that idea in terms of smaller ideas (paragraphs!). Later, as she was working, I asked her about one of her statements. She spat out a general "explanation" in a tone that said You Know, Or At Least You Should Know Because I Know. We talked about her job as the writer--the expert--to give us the details, about how we don't know what she knows, and about how that is where the length of papers can come from, in the provision of clear, meaningful details that help people know what they didn't know.

No. First of all, both of them need to figure out what they are saying. It's like they are planning trips without deciding where they are going. Actually, in the second student's case, she took the trip with only a vague idea of where she was going, didn't really map out her route, and didn't remember her trip well enough to make it worth her while.

For the first student, the one who worried about her introduction: Her teacher was standing with us. I asked the student which one, her teacher or me, she could introduce better. She said her teacher. All she could do for me, since she just met me, was remember my name and my job. Not an absolute failure of an intro, but not a thorough one, either. I told her she shouldn't worry about introducing something she doesn't know well. She should figure out what she has to say (she was leaning toward arguing something about coaching methods for children, about keeping it about teamwork and the like instead of becoming a raging lunatic who only cares about winning and forgets that the kids are more interesting in the orange slices after the game) before she tries to write her intro. I told her to write her introduction last if she wanted. She seemed calmer and more willing to explore an idea instead of stressed about completing a paper.

For the second student, the one who wanted to first of all make it longer: longer about nothing is worth nothing, so first of all, we talked about her core idea. Second of all, we broke down what she meant and where she could take that idea in terms of smaller ideas (paragraphs!). Later, as she was working, I asked her about one of her statements. She spat out a general "explanation" in a tone that said You Know, Or At Least You Should Know Because I Know. We talked about her job as the writer--the expert--to give us the details, about how we don't know what she knows, and about how that is where the length of papers can come from, in the provision of clear, meaningful details that help people know what they didn't know.

Tuesday, October 7, 2008

How, or A List of Items Which Students Should Practice in the Space of Their Writing Instruction

1. Curiosity

2. Breaking Words into Pieces

3. Dissecting Ideas

4. Finding meaning in what appears meaningless (or at least meaning-indifferent)

5. Wrestling with Words

Notes:

1. Can it be awakened? Can we find ways to make people ask questions of the world, to inquire more, to explore without a hot academic branding iron threatening them from behind their chair? Can we be curious ourselves and pass that along to the minds we are charged with cultivating? Can we teach people how not only to answer but to ask?

2. Words: pinatas, easter eggs, matryoshka dolls, shipping crates, envelopes, cocoons, cargo planes, Armored Personnel Carriers, lockets, mason jars, lunch boxes, milk cartons, et cetera.

3. This must be one of the great powers: to find the ways in which Something can become This Thing and That Thing and Those Things. It is an unstoppable force because we can find ways to stop all kinds of physical projectiles and pathogens, but we cannot defend our ideas from the sharp scalpel of an intelligent mind.

4a. There is always meaning.

4b. It is there, beneath the surface, poking a corner through, showing a bit of color, waiting.

5. In a cage, with folding chairs. In the backyard, against older brothers. In a mask, flying from the top rope. In the arena, dusty and gored. By the bike racks, for your lunch money. By a river, for your name. When you come out the other side, you are less stoppable than you were before.

2. Breaking Words into Pieces

3. Dissecting Ideas

4. Finding meaning in what appears meaningless (or at least meaning-indifferent)

5. Wrestling with Words

Notes:

1. Can it be awakened? Can we find ways to make people ask questions of the world, to inquire more, to explore without a hot academic branding iron threatening them from behind their chair? Can we be curious ourselves and pass that along to the minds we are charged with cultivating? Can we teach people how not only to answer but to ask?

2. Words: pinatas, easter eggs, matryoshka dolls, shipping crates, envelopes, cocoons, cargo planes, Armored Personnel Carriers, lockets, mason jars, lunch boxes, milk cartons, et cetera.

3. This must be one of the great powers: to find the ways in which Something can become This Thing and That Thing and Those Things. It is an unstoppable force because we can find ways to stop all kinds of physical projectiles and pathogens, but we cannot defend our ideas from the sharp scalpel of an intelligent mind.

4a. There is always meaning.

4b. It is there, beneath the surface, poking a corner through, showing a bit of color, waiting.

5. In a cage, with folding chairs. In the backyard, against older brothers. In a mask, flying from the top rope. In the arena, dusty and gored. By the bike racks, for your lunch money. By a river, for your name. When you come out the other side, you are less stoppable than you were before.

Thursday, September 25, 2008

Writing is in the Smallest of Increments

Learning to write well is learning to think well, to notice well, and then to draw meaning out of what you notice. Learning to write well is learning that a ruler is used to measure inches and also eighths of inches and sixteenths of inches. It is learning to see subtleties and small changes, to find big meaning in the smallest of things, to measure large objects or ideas in small increments.

This is what I find people need to discover. Students come in with generalities, with things measured in inches or even feet, and they need to look closer and closer until they begin to see what only they can see.

This is what I find people need to discover. Students come in with generalities, with things measured in inches or even feet, and they need to look closer and closer until they begin to see what only they can see.

Friday, September 19, 2008

Reading Fiction is Good for You

I came across this on Esquire's website today: a list of the seventy-five books that every man should read.

I don't care if other literary folks agree or disagree. I do care that some literary folks decided to sit down and make this list. Seventy-five books is a lot of books in a country where most people read less than one a year. I often wish that I knew more people who actively pursued reading books, fiction in particular. We learn from stories. They grow into us like roots or climbing vines. They stick in the crevices of our brains to be blown free and useful and necessary when the right wind comes up.

Three of my favorite books are on the list: What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, Moby-Dick, and The Adventure of Huckleberry Finn. Also, there are some books and authors I want to read: The Adventures of Augie March, Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, The Brothers Karamazov, American Pastoral, more, more.

I always get big ideas when I see book lists like this. Not just any book list, but books lists chosen by discerning people who are not trying to establish a canon, per se, but simple say here is a collection of books that orbit a particular sun. I've been wondering every now and then over the past few months about the possibility of getting my male friends to read the same fiction at the same time, books like Robinson Crusoe or something by Jack Kerouac, adventure and manliness and all that. I don't know if it will work. Everyone's life is already fullfullfull (what would we give up? what would we be willing to give up to create space for reading fiction?). This list was at least a small piece of evidence that there are other men out there who read fiction.

I don't care if other literary folks agree or disagree. I do care that some literary folks decided to sit down and make this list. Seventy-five books is a lot of books in a country where most people read less than one a year. I often wish that I knew more people who actively pursued reading books, fiction in particular. We learn from stories. They grow into us like roots or climbing vines. They stick in the crevices of our brains to be blown free and useful and necessary when the right wind comes up.

Three of my favorite books are on the list: What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, Moby-Dick, and The Adventure of Huckleberry Finn. Also, there are some books and authors I want to read: The Adventures of Augie March, Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, The Brothers Karamazov, American Pastoral, more, more.

I always get big ideas when I see book lists like this. Not just any book list, but books lists chosen by discerning people who are not trying to establish a canon, per se, but simple say here is a collection of books that orbit a particular sun. I've been wondering every now and then over the past few months about the possibility of getting my male friends to read the same fiction at the same time, books like Robinson Crusoe or something by Jack Kerouac, adventure and manliness and all that. I don't know if it will work. Everyone's life is already fullfullfull (what would we give up? what would we be willing to give up to create space for reading fiction?). This list was at least a small piece of evidence that there are other men out there who read fiction.

Saturday, September 6, 2008

Judging a Person by the Book Cover on His/Her T-Shirt

I found these literary tees on UrbanOutfitters.com:

1. Catch-22

2. Invisible Man

3. Death of a Salesman

1. Catch-22

2. Invisible Man

3. Death of a Salesman

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

Definitely One of the Top Five Pirate Supply Stores/Tutoring Centers I've Been to Recently

I've been inspired by 826Valencia in San Francisco for a long, long time now. They are the tutoring cog in the dynamic literary machine that is McSweeney's + The Believer. They are also a pirate supply store, selling eye patches, peglegs, and lard, amongst other piratey things.

Here is the story about how a Pirate Supply Store/Tutoring Center came to exist, told by Dave Eggers, author and founder of McSweeney's and 826Valencia, in his TED Prize One Wish speech:

Here is the story about how a Pirate Supply Store/Tutoring Center came to exist, told by Dave Eggers, author and founder of McSweeney's and 826Valencia, in his TED Prize One Wish speech:

Monday, August 25, 2008

Quoted Quotables

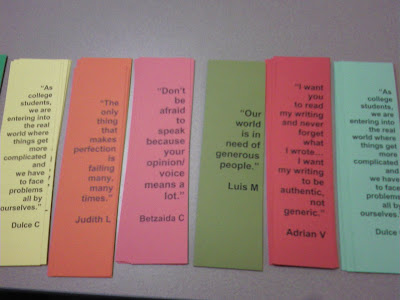

The footnote to this entry from July indicates that I wanted to do something with the widsom and insight of students that I run across as a person involved in education. Here is that something in its current incarnation as bookmarks. Luis' words can be found along with four other quotes that I wrote down after reading over student journals or papers or message postings over the last few semesters.

In our consumer culture, we are accustomed to buying/receiving/taking from those we are told we should buy/receive/take from. They are smart or beautiful or popular and we listen to them because they are known as smart or beautiful or popular. It's easy to ignore what we have not been told to pay attention to, and that includes the vast amount of intellectual work being done in educational institutions all over the place. It's a tragedy that so many words are printed simply for the sake of fulfilling class assignments or school projects, as opposed to these assignments asking students for words worth printing in the bigger picture of things--observing, examining, hoping, you know, the work that professional writers do.

Matt and I found some student words worth printing because they were poignant. We put them on bookmarks. Stop by if you want one (or if you want to know what they say). Each quote is on each color.

This is a project that is an example of why I believe in education. The world is full of capable, brilliant people who simply need unlocking or guidance or a push in the right direction.

Thursday, August 21, 2008

Expert Testimony: Everybody's Got Their Something

I always visit several Student Success classes each school year to tell them about -gasp- plagiarism*. I tell them about the consequences, about how it happens unintentionally most of the time, about how I've really not seen it or heard about it from other teachers because most of the people who choose to come here are honest, hard-working folks who know they are here for a very good reason.

This time around, I thought I would add an element to my short presentation: I brought notecards and asked them to write a) their name and b) something, anything, they consider themselves an expert in. In the big scheme of things, the biggest benefit most of those brand-new college students in those classes receive from hearing from me is the fact that they begin to build a relationship** with someone in The Learning Center. I thought asking them about their expertise would help that along a bit, as well as show them that I do, in fact care about what they care about.

Here are the results of my little survey (in no particular order):

Tennis (2)

A Role Model {because of his older brothers being his role model}

Kids

Cooking (2)

Being a Student

Computers (3) {this often related to teaching parents what to do}

Math

Sports (3)

Writing {I asked her what she wrote: stories}

Giving Advice {but she doesn't take her own, she said...hmmm}

Shopping {she immediately began to defend herself}

Eating {written as she was ingesting a bagel}

Softball

Basketball (4)

Volleyball (2)

Being on Time for Appointments

Riding Quads

Texting (4) {one even spelled it "txting" because we just don't need that e}

Being Serious {intriguing, really}

Organizing

Driving {yes, he had tickets}

Doing Laundry

Reading

Video Games

Drawing

Digital Cameras/Accessories {a Best Buy employee, not a photographer}

Sleeping

I enjoyed going around and talking to them about their expertise. They were honest, and I think it helped them understand that the people they would be using as sources in their papers were experts in a similar way. It brought them a little closer to the position of the writer of articles in newspapers and magazines and scholarly journals.

*from the Latin plagiarus, or kidnapping

**Oh, did it work. This time, two wonderful students--sisters, even--brought me a small bag of homemade, delicious oatmeal raisin cookies with a handwritten thank you note. Fantastic.

This time around, I thought I would add an element to my short presentation: I brought notecards and asked them to write a) their name and b) something, anything, they consider themselves an expert in. In the big scheme of things, the biggest benefit most of those brand-new college students in those classes receive from hearing from me is the fact that they begin to build a relationship** with someone in The Learning Center. I thought asking them about their expertise would help that along a bit, as well as show them that I do, in fact care about what they care about.

Here are the results of my little survey (in no particular order):

Tennis (2)

A Role Model {because of his older brothers being his role model}

Kids

Cooking (2)

Being a Student

Computers (3) {this often related to teaching parents what to do}

Math

Sports (3)

Writing {I asked her what she wrote: stories}

Giving Advice {but she doesn't take her own, she said...hmmm}

Shopping {she immediately began to defend herself}

Eating {written as she was ingesting a bagel}

Softball

Basketball (4)

Volleyball (2)

Being on Time for Appointments

Riding Quads

Texting (4) {one even spelled it "txting" because we just don't need that e}

Being Serious {intriguing, really}

Organizing

Driving {yes, he had tickets}

Doing Laundry

Reading

Video Games

Drawing

Digital Cameras/Accessories {a Best Buy employee, not a photographer}

Sleeping

I enjoyed going around and talking to them about their expertise. They were honest, and I think it helped them understand that the people they would be using as sources in their papers were experts in a similar way. It brought them a little closer to the position of the writer of articles in newspapers and magazines and scholarly journals.

*from the Latin plagiarus, or kidnapping

**Oh, did it work. This time, two wonderful students--sisters, even--brought me a small bag of homemade, delicious oatmeal raisin cookies with a handwritten thank you note. Fantastic.

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

Making Research Relevant: The Shoes on Your Feet, The Words in Your Mouth, The Borders They Crossed

I love research. To be perfectly clear, I love the idea of research. I love that there are people who dig, dig, dig for answers to questions. I love that they are passionate about finding those answers and truthful in the the relation of those findings.

Yesterday, I wrote down three questions that, in my notebook, I labeled "Research Questions Worth the Time and Intellectual Effort of American High School Students." I would amend that to include college students as well. They are:

Who made your shoes?

Why do most Americans speak English?

How many Americans come from immigrant families?

They are simple and they are wide-open--and they are direct in their indirection. In the first one, I'm not asking them to research human rights, sweatshops, corporations, outsourcing of jobs, or any other hot button issue with direct language. Instead, I'm skipping the technical terms that experts use on television or in published articles and simply asking them to look down at their feet and start thinking that somewhere somebody had to construct the shoes they see. That can lead them to a lot of places, including human rights, sweatshops, corporations, outsourcing of jobs, and many other hot button issues. It's a back door approach. Really, it's a student-discovery-centered approach, and it's connected to their lives, not some abstract idea.

Asking them why Americans speak English is the same approach to get them to think about a) the cultures and languages that enter(ed) America, b) what happens to cultures and languages in America, and c) how language is liquid and always changing. Asking them about immigrant families brings the present and the past together and highlights the nature of the formation of the current United States.

Discussions of terms and theories and abstract ideas can be tacked on to these concrete questions. Some people are more apt to think in terms and theories and abstract ideas than others; everybody can look down at their shoes and ask who made them.

Yesterday, I wrote down three questions that, in my notebook, I labeled "Research Questions Worth the Time and Intellectual Effort of American High School Students." I would amend that to include college students as well. They are:

Who made your shoes?

Why do most Americans speak English?

How many Americans come from immigrant families?

They are simple and they are wide-open--and they are direct in their indirection. In the first one, I'm not asking them to research human rights, sweatshops, corporations, outsourcing of jobs, or any other hot button issue with direct language. Instead, I'm skipping the technical terms that experts use on television or in published articles and simply asking them to look down at their feet and start thinking that somewhere somebody had to construct the shoes they see. That can lead them to a lot of places, including human rights, sweatshops, corporations, outsourcing of jobs, and many other hot button issues. It's a back door approach. Really, it's a student-discovery-centered approach, and it's connected to their lives, not some abstract idea.

Asking them why Americans speak English is the same approach to get them to think about a) the cultures and languages that enter(ed) America, b) what happens to cultures and languages in America, and c) how language is liquid and always changing. Asking them about immigrant families brings the present and the past together and highlights the nature of the formation of the current United States.

Discussions of terms and theories and abstract ideas can be tacked on to these concrete questions. Some people are more apt to think in terms and theories and abstract ideas than others; everybody can look down at their shoes and ask who made them.

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

This is How We Do It

Writing Process is an interesting term. It implies steps, an institutional kind of order even, a 1-2-3-done kind of thinking--but it also allows for creativity and variety for individuals to invent their own way to bring a piece of writing to completion (and to continue to reinvent that process as needed).

I'm interested in Writing Process in all its incarnations: the overall how-to's that are passed along from writing teachers to writing students, the innovative ways that writers (both students and professionals) think of to help them build an idea into an essay or a story, and the unthought-of, unnoticed little steps that people who are engaged in the act of writing go through that are definitely part of the process, yet outside of what those in the field of writing would discuss when asked to discuss Writing Process.

Here is an example of what I mean about the last of those three. It comes from Robert, a student in my Writing 100 class from this past Spring semester:

"When I'm trying to complete a writing assignment, I sweat a lot, then go into contortions, and then start swearing."

I'm interested in Writing Process in all its incarnations: the overall how-to's that are passed along from writing teachers to writing students, the innovative ways that writers (both students and professionals) think of to help them build an idea into an essay or a story, and the unthought-of, unnoticed little steps that people who are engaged in the act of writing go through that are definitely part of the process, yet outside of what those in the field of writing would discuss when asked to discuss Writing Process.

Here is an example of what I mean about the last of those three. It comes from Robert, a student in my Writing 100 class from this past Spring semester:

"When I'm trying to complete a writing assignment, I sweat a lot, then go into contortions, and then start swearing."

Thursday, August 7, 2008

Good Guys Wear Hoodies

Here's the text from an ad for hoodies made by Howies, a Welsh clothing company (font and bold as printed):

If we're going to ban items of clothing, shouldn't we start with the business suit?

While we don't condone shoplifting, terrorising old ladies or generally making other people's lives a misery, the tabloids seem to be picking on the wrong people. Casual research suggests serious fraud, insider trading or acts of corporate man-slaughter are unlikely to be carried out by people wearing hooded sweatshirts. Photographs of senior executives of British manufacturers of land mines, anti-personnel grenades and cluster bombs have shown no evidence of hoodie-wearers. Businessmen offering large amounts of cash in return for peerages, and the politicians who accept the cash, tend towards less casual items of clothing. When the decision was made to invade Iraq, no-one wore a hoodie. And the men who think Guantanamo Bay is still a good idea do not wear hoods themselves, though they have been known to offer them to guests. Sure, there's the odd villain who wants to conceal his face. But there's bigger villains around who have no such shame.

Jon Matthews