Today, a student came in with a worksheet. I'm not a huge fan of worksheets because they usually focus on technical aspects of grammar that are not inherently bad things to know (people would do well to know them) but are generally less than useful in terms of their applied function for writing students.

This worksheet, however, is possibly one of the most useful I've ever seen. It was simple. It took some sentences the student composed for a prior worksheet and had them replace general terms with specific nouns. Students need to know how to do that. They need that practice.

The example was corny (it replaced "elderly man" with "Old Jimmy Two-Teeth"), but the worksheet gave this student a chance to work on a writing skill that I see people struggle with everyday: being specific. I'm all for this and will probably add a similar activity to any classroom work I do in the future.

Showing posts with label writing in the real world. Show all posts

Showing posts with label writing in the real world. Show all posts

Friday, November 13, 2009

Thursday, October 1, 2009

Make It Your Own

I read across a wide spectrum of subjects. One of them happens to be sports uniforms. Uni Watch is a blog that not simply covers sports uniforms ("athletic aesthetics" they would say), but delves deep into the subject.

Here's an essay submitted by a Uni Watch reader named Matt King. He details his decision to own authentic jerseys with his own name on the back. The normal practice (and some would say the only acceptable practice among true uniphiles) is to purchase an authentic jersey with the name of an authentic player on the back.

I think he makes a good case for the practice losing its taboo status. I like that he took it upon himself to defend his Own Name On Back decision. He stops short of championing the movement, but he goes into the context of his own decision (which originated before authentic apparel was widely available) as well as giving us general reasons for putting your own last name on the jersey of your favorite team despite never playing a down/inning/minute for the club (now that authentic apparel is readily available).

Here's an essay submitted by a Uni Watch reader named Matt King. He details his decision to own authentic jerseys with his own name on the back. The normal practice (and some would say the only acceptable practice among true uniphiles) is to purchase an authentic jersey with the name of an authentic player on the back.

I think he makes a good case for the practice losing its taboo status. I like that he took it upon himself to defend his Own Name On Back decision. He stops short of championing the movement, but he goes into the context of his own decision (which originated before authentic apparel was widely available) as well as giving us general reasons for putting your own last name on the jersey of your favorite team despite never playing a down/inning/minute for the club (now that authentic apparel is readily available).

Friday, April 17, 2009

Links of Note

1. Stupidity in Research: an article by a microbiologist (and they don't just let anybody do that) about the necessity of that I Don't Know feeling. If I were to make a pie graph of my job, which I have considered doing, I imagine a fairly large chunk of that circle would be labeled, "Telling People It Is Okay To Not Know." I ask students this question: What do you think? They reply: I don't know. I counter: I know you don't know, but I didn't ask what you know; I asked what you think.

2. John McPhee: an NPR piece and a Princeton Weekly Bulletin article on my newest authorial discovery. I think this guy is cool. The foundation of his livelihood is his curiosity. He is not a specialist in anything other than nonfiction. I just finished his first book, A Sense of Where You Are: Bill Bradley at Princeton, which follows now Senator Bill Bradley during his college basketball career and paints him as a sort of savant on the court, hyper-aware and capable of physical feats others don't know are possible.

Part of what I love about this book is that it came naturally to McPhee. He has lived most of his life in Princeton, and Bradley's presence slotted right in. The book grew organically from their intersection at the school. Another part of what I love is that McPhee is not a sportswriter. He is a writer who covers anything and everything (read the articles; you'll see), and this book happened to be about a basketball player.

2. John McPhee: an NPR piece and a Princeton Weekly Bulletin article on my newest authorial discovery. I think this guy is cool. The foundation of his livelihood is his curiosity. He is not a specialist in anything other than nonfiction. I just finished his first book, A Sense of Where You Are: Bill Bradley at Princeton, which follows now Senator Bill Bradley during his college basketball career and paints him as a sort of savant on the court, hyper-aware and capable of physical feats others don't know are possible.

Part of what I love about this book is that it came naturally to McPhee. He has lived most of his life in Princeton, and Bradley's presence slotted right in. The book grew organically from their intersection at the school. Another part of what I love is that McPhee is not a sportswriter. He is a writer who covers anything and everything (read the articles; you'll see), and this book happened to be about a basketball player.

Monday, December 22, 2008

Everything Comes From Seed

I'm not quite halfway through The Best American Essays of the Century, a book that I bought at Bookman's for nine dollars in trade credit over a year ago, maybe more. I bought it because I teach people how to write essays, and I have a philosophy of learning that involves learning from examples, and examples labeled "the best" by Joyce Carol Oates and Robert Atwan are worth learning from. I gave myself permission to read an essay a day or so. I have not kept that pace, but I do find the time to read here and there, so I'm slowly making my way through.

I have made discoveries while reading this book--really, while piling the readings up in my head, one essay by one essay, each a few years down the road from the one I read before it, each a record of how ideas are moving along the century.

1. Race Relations and Civil Rights permeate much deeper into the soil of American History than I realized (or was taught, really). It seems like one of every three or four essays tackles some varied perspective on minorities and majorities in our nation. The four that stick in my head are W.E.B. Du Bois's "On the Coming of John" (education, black/white, poverty), John Jay Chapman's "Coatesville" (repentence of racial crimes whose perpetrators were acquitted), Richard Wright's "The Ethics of Living Jim Crow: An Autobiographical Sketch" (education of a different, social, everyday sort), and Langston Hughes's "Bop" (pop culture's roots in dark dark things)

2. Writing that is worth reading is the process of a careful mind exploring simple moments, questions, or ideas. The ideas themselves do not need to be complicated. Hughes lays out a conversation between two black men about bebop music. James Agee, in "Knoxville: Summer of 1915," puts the evenings in his boyhood neighborhood under the poetic miscroscope. E.B. White writes about revisiting a lake, a place that he visited with his father, as a father himself in "Once More to the Lake." These are not complicated things, but the essays are beautiful, exact, detailed, and careful.

3. Organization is any structure an author uses to prop up his ideas; there are no rules--only control. I've told students before that, while teachers may ask for certain parts of particular structures, in the real world, all that readers ask is that the author seem like he is in control, that he knows where the writing is going. However an author can do that is okay by the public. These essays are examples of that. Wright goes so far as to build his essay in sections marked by roman numerals. They are conversational in tone and include dialect in dialogue, and are of varied length, but the roman numerals shows the reader that Wright knows where he's starting and stopping. He knows the limits of each story, and he lets each one live fully within those limits.

I think these discoveries could work to benefit a class full of learning writers.

The fact that race relations is such an integral thread to American life could spur a class to write about their own experiences living in multicultural environments, about their own life-lessons about "how it is" in terms of stereotypes and racial interactions and what can be done to move "how it is" toward "how it could be."

The idea of growing an essay from a simple idea could be important to the direction given. The work a student should do is not the work of diciphering an assigment; instead, it should be the work of taking a simple question or idea (either given by a teacher or unearthed from life) and mapping it, dissecting it, exploring it, and recording what is found.

Organization and control may be the most difficult to grade, but may also be fun to teach. It would allow a conversation between teacher and student in which the student is the owner of the idea--and of the presentation of the idea--and the teacher is the mentor+audience. In this mode, the student can discover and attempt to record, and the teacher can react, ask questions, and give gentle suggestions to mold people who can control the wild ideas in their heads that sneak around like mice or flail like loosed fire hoses. The only rule is: learn to control the idea, to package it so it can be unpacked and understood.

I have made discoveries while reading this book--really, while piling the readings up in my head, one essay by one essay, each a few years down the road from the one I read before it, each a record of how ideas are moving along the century.

1. Race Relations and Civil Rights permeate much deeper into the soil of American History than I realized (or was taught, really). It seems like one of every three or four essays tackles some varied perspective on minorities and majorities in our nation. The four that stick in my head are W.E.B. Du Bois's "On the Coming of John" (education, black/white, poverty), John Jay Chapman's "Coatesville" (repentence of racial crimes whose perpetrators were acquitted), Richard Wright's "The Ethics of Living Jim Crow: An Autobiographical Sketch" (education of a different, social, everyday sort), and Langston Hughes's "Bop" (pop culture's roots in dark dark things)

2. Writing that is worth reading is the process of a careful mind exploring simple moments, questions, or ideas. The ideas themselves do not need to be complicated. Hughes lays out a conversation between two black men about bebop music. James Agee, in "Knoxville: Summer of 1915," puts the evenings in his boyhood neighborhood under the poetic miscroscope. E.B. White writes about revisiting a lake, a place that he visited with his father, as a father himself in "Once More to the Lake." These are not complicated things, but the essays are beautiful, exact, detailed, and careful.

3. Organization is any structure an author uses to prop up his ideas; there are no rules--only control. I've told students before that, while teachers may ask for certain parts of particular structures, in the real world, all that readers ask is that the author seem like he is in control, that he knows where the writing is going. However an author can do that is okay by the public. These essays are examples of that. Wright goes so far as to build his essay in sections marked by roman numerals. They are conversational in tone and include dialect in dialogue, and are of varied length, but the roman numerals shows the reader that Wright knows where he's starting and stopping. He knows the limits of each story, and he lets each one live fully within those limits.

I think these discoveries could work to benefit a class full of learning writers.

The fact that race relations is such an integral thread to American life could spur a class to write about their own experiences living in multicultural environments, about their own life-lessons about "how it is" in terms of stereotypes and racial interactions and what can be done to move "how it is" toward "how it could be."

The idea of growing an essay from a simple idea could be important to the direction given. The work a student should do is not the work of diciphering an assigment; instead, it should be the work of taking a simple question or idea (either given by a teacher or unearthed from life) and mapping it, dissecting it, exploring it, and recording what is found.

Organization and control may be the most difficult to grade, but may also be fun to teach. It would allow a conversation between teacher and student in which the student is the owner of the idea--and of the presentation of the idea--and the teacher is the mentor+audience. In this mode, the student can discover and attempt to record, and the teacher can react, ask questions, and give gentle suggestions to mold people who can control the wild ideas in their heads that sneak around like mice or flail like loosed fire hoses. The only rule is: learn to control the idea, to package it so it can be unpacked and understood.

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

Meaning is Everywhere, Even in Honey Jars or Cartoon Savannas

Here are two thesis ideas for essays I overheard in the Writing Lab today:

1. All the major characters from Winnie the Pooh are different aspects of Christopher Robin's personality. The person who said this went through an exhaustive list of each character and which part of Christopher Robin's personality they correspond to. It was really quite impressive.

2. The Lion King is Shakespeare's Hamlet in Africa. And Disney-fied. No, Simba doesn't feign insanity, or put on a play-within-a-play/movie, and he doesn't die in the end, and Scar doesn't marry Simba's mother, but there are enough similarities between the two stories there for that argument to stand (there is a father's ghost in each, which is important for any comparison including Hamlet).

1. All the major characters from Winnie the Pooh are different aspects of Christopher Robin's personality. The person who said this went through an exhaustive list of each character and which part of Christopher Robin's personality they correspond to. It was really quite impressive.

2. The Lion King is Shakespeare's Hamlet in Africa. And Disney-fied. No, Simba doesn't feign insanity, or put on a play-within-a-play/movie, and he doesn't die in the end, and Scar doesn't marry Simba's mother, but there are enough similarities between the two stories there for that argument to stand (there is a father's ghost in each, which is important for any comparison including Hamlet).

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

On Beer and Research

Another set of valid research questions that are based in reality came from a student working a paper persuading her friends not to do drugs. The questions are tangents, but they are worth mentioning because they a) are genuine, and b) seem like they might have simple answers, but really don't, so they require some research.

Her questions:

1. Why did people make beer?

2. Why do people drink beer?

On No.1: She thought this would be a simple answer to find on the Internet, so she went sleuthing, only to find differentiations between ales and lagers and pilsners (oh my!). The history she found was brief (as in, Ancient Egyptians had beer! Look how old beer is!). She found out that her question was more complex than she originally assumed: instead of When's and Where's, she wanted the Why, which is a great thing to look for. It takes finding When's and Where's along with Reasons and Purposes. Since this wasn't her main project, she cut off her search at this point, but not before I told her about how people write books based on simple research questions like this*.

On No.2: Here, she opened the door to sociology. In her limited experience, the answer to that questions was To Get Drunk, but she sensed there was some bigger reason behind that. We talked about how there are many reasons why people drink beer, and that she could write a whole paper based on different reasons why different people drink different beers.

On Why This Paper Would Be an Interesting Paper to Read:

First, it came from a simple and genuine question. She really wanted to know this--it wasn't thrust upon her by an authority figure wielding a syllabus and white board marker--so the results of her paper would most likely have some life to it (especially if her work was mentored by someone who wanted to help her come alive as a writer and explorer).

Second, the question is not some obscure idea at the periphery of human consciousness or some difficult/too large/too complex idea that she knows nothing about. She knows about beer. She's seen people drink beer. She doesn't have to cross the gap of content knowledge to write about this subject. She's expanding her knowledge on a subject she is already familiar with, so the paper would show the tone of that expansion, not of a deer-in-headlights student bewildered by a topic they do not find intriguing or accessible.

Third, it's relevant to her demographic and her life. Imagine: classes where people pursue projects involving the deepening of their knowledge of the things of their own lives. Imagine: a young person taking the initiative to study the why's and wherefore's of the consumption of alcohol. Imagine: that young person waking up to the possibility of understanding why's and wherefore's, period, of opening up the thought processes of those around, of seeing that what we do and say is not Dumb Luck or What We Are Supposed To Do And Say, but that it has reason--conscious or unconscious--that it has cause, and that that cause can be put under a microscope to see its cell walls and its nucleus.

Fourth, she'll probably remember this paper pretty well. She might even win a few bets, or astound a few friends, or become a beer connoisseur. It's not like beer advertisements are going to go away, so every time she sees someone selling Budweiser or Heineken or Guiness on television, she'll be reminded that she knows a little something about where all that came from.

*Among those that come to mind: Salt, Cod, A History of the World in 6 Glasses.

Her questions:

1. Why did people make beer?

2. Why do people drink beer?

On No.1: She thought this would be a simple answer to find on the Internet, so she went sleuthing, only to find differentiations between ales and lagers and pilsners (oh my!). The history she found was brief (as in, Ancient Egyptians had beer! Look how old beer is!). She found out that her question was more complex than she originally assumed: instead of When's and Where's, she wanted the Why, which is a great thing to look for. It takes finding When's and Where's along with Reasons and Purposes. Since this wasn't her main project, she cut off her search at this point, but not before I told her about how people write books based on simple research questions like this*.

On No.2: Here, she opened the door to sociology. In her limited experience, the answer to that questions was To Get Drunk, but she sensed there was some bigger reason behind that. We talked about how there are many reasons why people drink beer, and that she could write a whole paper based on different reasons why different people drink different beers.

On Why This Paper Would Be an Interesting Paper to Read:

First, it came from a simple and genuine question. She really wanted to know this--it wasn't thrust upon her by an authority figure wielding a syllabus and white board marker--so the results of her paper would most likely have some life to it (especially if her work was mentored by someone who wanted to help her come alive as a writer and explorer).

Second, the question is not some obscure idea at the periphery of human consciousness or some difficult/too large/too complex idea that she knows nothing about. She knows about beer. She's seen people drink beer. She doesn't have to cross the gap of content knowledge to write about this subject. She's expanding her knowledge on a subject she is already familiar with, so the paper would show the tone of that expansion, not of a deer-in-headlights student bewildered by a topic they do not find intriguing or accessible.

Third, it's relevant to her demographic and her life. Imagine: classes where people pursue projects involving the deepening of their knowledge of the things of their own lives. Imagine: a young person taking the initiative to study the why's and wherefore's of the consumption of alcohol. Imagine: that young person waking up to the possibility of understanding why's and wherefore's, period, of opening up the thought processes of those around, of seeing that what we do and say is not Dumb Luck or What We Are Supposed To Do And Say, but that it has reason--conscious or unconscious--that it has cause, and that that cause can be put under a microscope to see its cell walls and its nucleus.

Fourth, she'll probably remember this paper pretty well. She might even win a few bets, or astound a few friends, or become a beer connoisseur. It's not like beer advertisements are going to go away, so every time she sees someone selling Budweiser or Heineken or Guiness on television, she'll be reminded that she knows a little something about where all that came from.

*Among those that come to mind: Salt, Cod, A History of the World in 6 Glasses.

Friday, September 19, 2008

Reading Fiction is Good for You

I came across this on Esquire's website today: a list of the seventy-five books that every man should read.

I don't care if other literary folks agree or disagree. I do care that some literary folks decided to sit down and make this list. Seventy-five books is a lot of books in a country where most people read less than one a year. I often wish that I knew more people who actively pursued reading books, fiction in particular. We learn from stories. They grow into us like roots or climbing vines. They stick in the crevices of our brains to be blown free and useful and necessary when the right wind comes up.

Three of my favorite books are on the list: What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, Moby-Dick, and The Adventure of Huckleberry Finn. Also, there are some books and authors I want to read: The Adventures of Augie March, Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, The Brothers Karamazov, American Pastoral, more, more.

I always get big ideas when I see book lists like this. Not just any book list, but books lists chosen by discerning people who are not trying to establish a canon, per se, but simple say here is a collection of books that orbit a particular sun. I've been wondering every now and then over the past few months about the possibility of getting my male friends to read the same fiction at the same time, books like Robinson Crusoe or something by Jack Kerouac, adventure and manliness and all that. I don't know if it will work. Everyone's life is already fullfullfull (what would we give up? what would we be willing to give up to create space for reading fiction?). This list was at least a small piece of evidence that there are other men out there who read fiction.

I don't care if other literary folks agree or disagree. I do care that some literary folks decided to sit down and make this list. Seventy-five books is a lot of books in a country where most people read less than one a year. I often wish that I knew more people who actively pursued reading books, fiction in particular. We learn from stories. They grow into us like roots or climbing vines. They stick in the crevices of our brains to be blown free and useful and necessary when the right wind comes up.

Three of my favorite books are on the list: What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, Moby-Dick, and The Adventure of Huckleberry Finn. Also, there are some books and authors I want to read: The Adventures of Augie March, Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, The Brothers Karamazov, American Pastoral, more, more.

I always get big ideas when I see book lists like this. Not just any book list, but books lists chosen by discerning people who are not trying to establish a canon, per se, but simple say here is a collection of books that orbit a particular sun. I've been wondering every now and then over the past few months about the possibility of getting my male friends to read the same fiction at the same time, books like Robinson Crusoe or something by Jack Kerouac, adventure and manliness and all that. I don't know if it will work. Everyone's life is already fullfullfull (what would we give up? what would we be willing to give up to create space for reading fiction?). This list was at least a small piece of evidence that there are other men out there who read fiction.

Saturday, September 6, 2008

Judging a Person by the Book Cover on His/Her T-Shirt

I found these literary tees on UrbanOutfitters.com:

1. Catch-22

2. Invisible Man

3. Death of a Salesman

1. Catch-22

2. Invisible Man

3. Death of a Salesman

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

Definitely One of the Top Five Pirate Supply Stores/Tutoring Centers I've Been to Recently

I've been inspired by 826Valencia in San Francisco for a long, long time now. They are the tutoring cog in the dynamic literary machine that is McSweeney's + The Believer. They are also a pirate supply store, selling eye patches, peglegs, and lard, amongst other piratey things.

Here is the story about how a Pirate Supply Store/Tutoring Center came to exist, told by Dave Eggers, author and founder of McSweeney's and 826Valencia, in his TED Prize One Wish speech:

Here is the story about how a Pirate Supply Store/Tutoring Center came to exist, told by Dave Eggers, author and founder of McSweeney's and 826Valencia, in his TED Prize One Wish speech:

Monday, August 25, 2008

Quoted Quotables

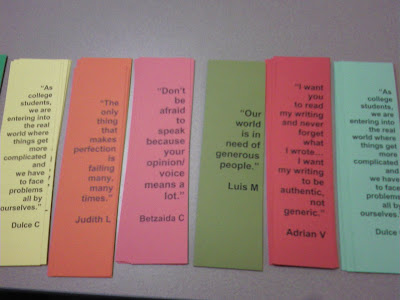

The footnote to this entry from July indicates that I wanted to do something with the widsom and insight of students that I run across as a person involved in education. Here is that something in its current incarnation as bookmarks. Luis' words can be found along with four other quotes that I wrote down after reading over student journals or papers or message postings over the last few semesters.

In our consumer culture, we are accustomed to buying/receiving/taking from those we are told we should buy/receive/take from. They are smart or beautiful or popular and we listen to them because they are known as smart or beautiful or popular. It's easy to ignore what we have not been told to pay attention to, and that includes the vast amount of intellectual work being done in educational institutions all over the place. It's a tragedy that so many words are printed simply for the sake of fulfilling class assignments or school projects, as opposed to these assignments asking students for words worth printing in the bigger picture of things--observing, examining, hoping, you know, the work that professional writers do.

Matt and I found some student words worth printing because they were poignant. We put them on bookmarks. Stop by if you want one (or if you want to know what they say). Each quote is on each color.

This is a project that is an example of why I believe in education. The world is full of capable, brilliant people who simply need unlocking or guidance or a push in the right direction.

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

Making Research Relevant: The Shoes on Your Feet, The Words in Your Mouth, The Borders They Crossed

I love research. To be perfectly clear, I love the idea of research. I love that there are people who dig, dig, dig for answers to questions. I love that they are passionate about finding those answers and truthful in the the relation of those findings.

Yesterday, I wrote down three questions that, in my notebook, I labeled "Research Questions Worth the Time and Intellectual Effort of American High School Students." I would amend that to include college students as well. They are:

Who made your shoes?

Why do most Americans speak English?

How many Americans come from immigrant families?

They are simple and they are wide-open--and they are direct in their indirection. In the first one, I'm not asking them to research human rights, sweatshops, corporations, outsourcing of jobs, or any other hot button issue with direct language. Instead, I'm skipping the technical terms that experts use on television or in published articles and simply asking them to look down at their feet and start thinking that somewhere somebody had to construct the shoes they see. That can lead them to a lot of places, including human rights, sweatshops, corporations, outsourcing of jobs, and many other hot button issues. It's a back door approach. Really, it's a student-discovery-centered approach, and it's connected to their lives, not some abstract idea.

Asking them why Americans speak English is the same approach to get them to think about a) the cultures and languages that enter(ed) America, b) what happens to cultures and languages in America, and c) how language is liquid and always changing. Asking them about immigrant families brings the present and the past together and highlights the nature of the formation of the current United States.

Discussions of terms and theories and abstract ideas can be tacked on to these concrete questions. Some people are more apt to think in terms and theories and abstract ideas than others; everybody can look down at their shoes and ask who made them.

Yesterday, I wrote down three questions that, in my notebook, I labeled "Research Questions Worth the Time and Intellectual Effort of American High School Students." I would amend that to include college students as well. They are:

Who made your shoes?

Why do most Americans speak English?

How many Americans come from immigrant families?

They are simple and they are wide-open--and they are direct in their indirection. In the first one, I'm not asking them to research human rights, sweatshops, corporations, outsourcing of jobs, or any other hot button issue with direct language. Instead, I'm skipping the technical terms that experts use on television or in published articles and simply asking them to look down at their feet and start thinking that somewhere somebody had to construct the shoes they see. That can lead them to a lot of places, including human rights, sweatshops, corporations, outsourcing of jobs, and many other hot button issues. It's a back door approach. Really, it's a student-discovery-centered approach, and it's connected to their lives, not some abstract idea.

Asking them why Americans speak English is the same approach to get them to think about a) the cultures and languages that enter(ed) America, b) what happens to cultures and languages in America, and c) how language is liquid and always changing. Asking them about immigrant families brings the present and the past together and highlights the nature of the formation of the current United States.

Discussions of terms and theories and abstract ideas can be tacked on to these concrete questions. Some people are more apt to think in terms and theories and abstract ideas than others; everybody can look down at their shoes and ask who made them.

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

This is How We Do It

Writing Process is an interesting term. It implies steps, an institutional kind of order even, a 1-2-3-done kind of thinking--but it also allows for creativity and variety for individuals to invent their own way to bring a piece of writing to completion (and to continue to reinvent that process as needed).

I'm interested in Writing Process in all its incarnations: the overall how-to's that are passed along from writing teachers to writing students, the innovative ways that writers (both students and professionals) think of to help them build an idea into an essay or a story, and the unthought-of, unnoticed little steps that people who are engaged in the act of writing go through that are definitely part of the process, yet outside of what those in the field of writing would discuss when asked to discuss Writing Process.

Here is an example of what I mean about the last of those three. It comes from Robert, a student in my Writing 100 class from this past Spring semester:

"When I'm trying to complete a writing assignment, I sweat a lot, then go into contortions, and then start swearing."

I'm interested in Writing Process in all its incarnations: the overall how-to's that are passed along from writing teachers to writing students, the innovative ways that writers (both students and professionals) think of to help them build an idea into an essay or a story, and the unthought-of, unnoticed little steps that people who are engaged in the act of writing go through that are definitely part of the process, yet outside of what those in the field of writing would discuss when asked to discuss Writing Process.

Here is an example of what I mean about the last of those three. It comes from Robert, a student in my Writing 100 class from this past Spring semester:

"When I'm trying to complete a writing assignment, I sweat a lot, then go into contortions, and then start swearing."

Thursday, August 7, 2008

Good Guys Wear Hoodies

Here's the text from an ad for hoodies made by Howies, a Welsh clothing company (font and bold as printed):

If we're going to ban items of clothing, shouldn't we start with the business suit?

While we don't condone shoplifting, terrorising old ladies or generally making other people's lives a misery, the tabloids seem to be picking on the wrong people. Casual research suggests serious fraud, insider trading or acts of corporate man-slaughter are unlikely to be carried out by people wearing hooded sweatshirts. Photographs of senior executives of British manufacturers of land mines, anti-personnel grenades and cluster bombs have shown no evidence of hoodie-wearers. Businessmen offering large amounts of cash in return for peerages, and the politicians who accept the cash, tend towards less casual items of clothing. When the decision was made to invade Iraq, no-one wore a hoodie. And the men who think Guantanamo Bay is still a good idea do not wear hoods themselves, though they have been known to offer them to guests. Sure, there's the odd villain who wants to conceal his face. But there's bigger villains around who have no such shame.

Jon Matthews

I love that they are making an argument against the opposite style of clothing they are selling. I love that it is so focused on one particular item of clothing. I also love that they use specific, tangible references to get their point across. Why is that effective? I originally read this little blurb in a magazine over a month ago; I have not forgotten it since.

If we're going to ban items of clothing, shouldn't we start with the business suit?

While we don't condone shoplifting, terrorising old ladies or generally making other people's lives a misery, the tabloids seem to be picking on the wrong people. Casual research suggests serious fraud, insider trading or acts of corporate man-slaughter are unlikely to be carried out by people wearing hooded sweatshirts. Photographs of senior executives of British manufacturers of land mines, anti-personnel grenades and cluster bombs have shown no evidence of hoodie-wearers. Businessmen offering large amounts of cash in return for peerages, and the politicians who accept the cash, tend towards less casual items of clothing. When the decision was made to invade Iraq, no-one wore a hoodie. And the men who think Guantanamo Bay is still a good idea do not wear hoods themselves, though they have been known to offer them to guests. Sure, there's the odd villain who wants to conceal his face. But there's bigger villains around who have no such shame.

Jon Matthews

I love that they are making an argument against the opposite style of clothing they are selling. I love that it is so focused on one particular item of clothing. I also love that they use specific, tangible references to get their point across. Why is that effective? I originally read this little blurb in a magazine over a month ago; I have not forgotten it since.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)